Basics of Tensors¶

Tensors are multi-dimensional arrays (MDAs). They are an important concept in Machine Learning, especially Neural Networks.

Studying tensors might seem intimidating at first, but as we discuss them, you will realize that they are no more than a generalization of arrays/vectors to multiple dimensions.

A note on Tensors in the present discussion¶

In most of Simple English Machine Learning, I will be talking about tensors as Multi-Dimensional Arrays or MDAs, where each element is real-value (i.e. each element \(\in \mathbb{R}\)). These are the kind you find in NumPy or MATLAB’s tensor package and are also called Cartesian tensors as they follow the Cartesian co-ordinate system.

This notion of tensors is not to be confused with tensors in physics and engineering (such as stress tensors), which are generally referred to as tensor fields in mathematics.

Tensor definition, notation and terminology¶

A tensor is a multidimensional array. Conceptually, it is the extension of the idea of a vector to multiple dimensions.

More formally, an order-d or d-way tensor is a real, d-dimensional array which we denote by \(\mathcal{A} \in \mathbb{R}^{N_1 \times N_2 \times \dots \times N_d}\).

Lower-order tensors are used so often that we have come up with separate names for them:

Order (\(d\)) |

Name |

Mathematical notation |

Mathematical representation |

Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

0 |

Scalar |

Greek alphabet |

\(\alpha \in \mathbb{R}\) |

\(5\) |

1 |

Vector |

Lowercase (possibly with a bar on top) |

\(\bf{a} \in \mathbb{R}^{N}\) or \(\bar{a} \in \mathbb{R}^{N}\) |

\(\left[ \begin{matrix} 6 & 3.0 & 2 & 0.5 \end{matrix} \right]\) |

2 |

Matrix (or dyad) |

Uppercase |

\(A\in \mathbb{R}^{N \times M}\) |

\(\left[ \begin{matrix} 145 & 4.2 & 69 \\ 18 & 23.9 & 8 \end{matrix} \right]\) |

3 |

Triad (3), Polyad, or just “tensor of order-\(d\)” |

Calligraphic uppercase |

\(\mathcal{A} \in \mathbb{R}^{N_1 \times N_2 \times \dots \times N_d}\) |

(Hard to visualize) |

You might have come across scalars, vectors and matrices before, so you might be familiar with reasoning about them. But what about higher-order tensors?

To build an intuition about tensors, let’s start with a real-world example using vectors:

Imagine we have gotten a hold of housing data from the latest census. We have a dataset of a million rows, each with various parameters of the house, such as number of bedrooms, number of bathrooms, area (in square feet), and number of stories.

We can represent each house in this example as a vector:

\[\begin{split}x = \left[ \begin{matrix} \bf{Bedrooms} & \bf{Bathrooms} & \bf{Area} & \bf{Stories} \\ 5 & 3 & 1800 & 2 \end{matrix} \right]\end{split}\]Each of these variables (also called features) has a particular range in which it can take values.

Variable |

Range |

|---|---|

Bedrooms |

2-8 |

Bathrooms |

1-5 |

Area |

800-5500 |

Stories |

1-3 |

You can imagine this vector to be similar to a combination bicycle lock, with a range different than the standard 0-9. Spinning the dials allows you to create different vectors. However, while each of the variables can take any real-value, the number of variables is 4.

Thus when we say we have a vector \(x \in \mathbb{R}^{4}\), we mean we have a linear array of 4 variables: \(x = \left[ \begin{matrix} x_1 & x_2 & x_3 & x_4 \end{matrix} \right]\)

The situation is similar for matrices:

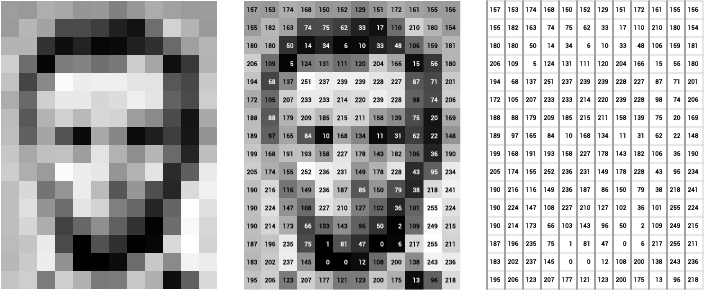

An \(\mathbb{R}^{12 \times 16}\) matrix means we have 12 x 16 = 192 variables, each of which might take values in the range 0-255 (if this matrix represents an image, like the one below).

- In this case, the image is still an order-2 tensor. The order of a tensor tells us the number of dimensions along which it has variables.

Here, there are two dimensions: one with 12 variables and one with 16 variables (usually denoted by x and y axes).

We can index each variable of this matrix using the notation: \(A_{(i,j)}\) where \(i \in \{0, \dots, 11\}\) and \(j \in \{0, \dots, 15\}\).

An image matrix of Abraham Lincoln. Source: http://ai.stanford.edu/~syyeung/cvweb/tutorial1.html¶

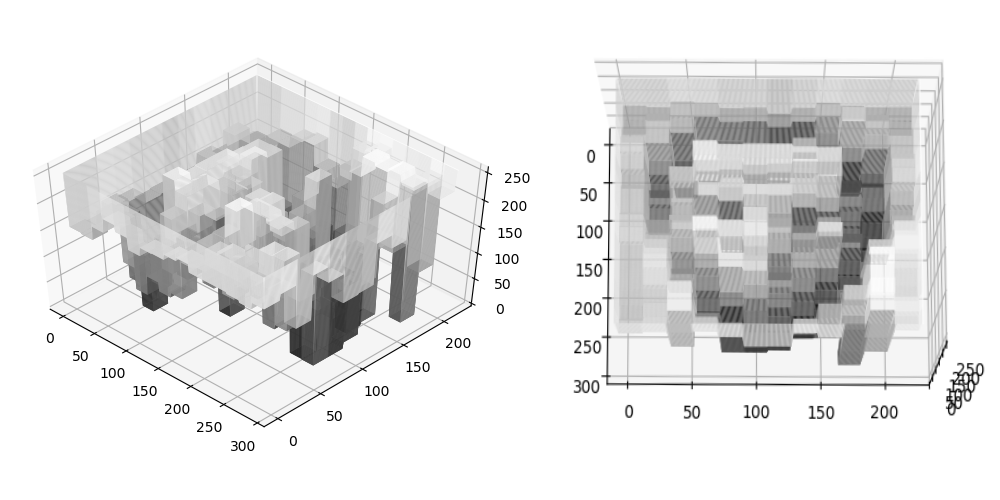

3D Intensity plot of Abraham Lincoln. Source: https://summations.github.io/snippets/cv/intensityplot/¶

A tensor is just an extension of this concept to more dimensions.

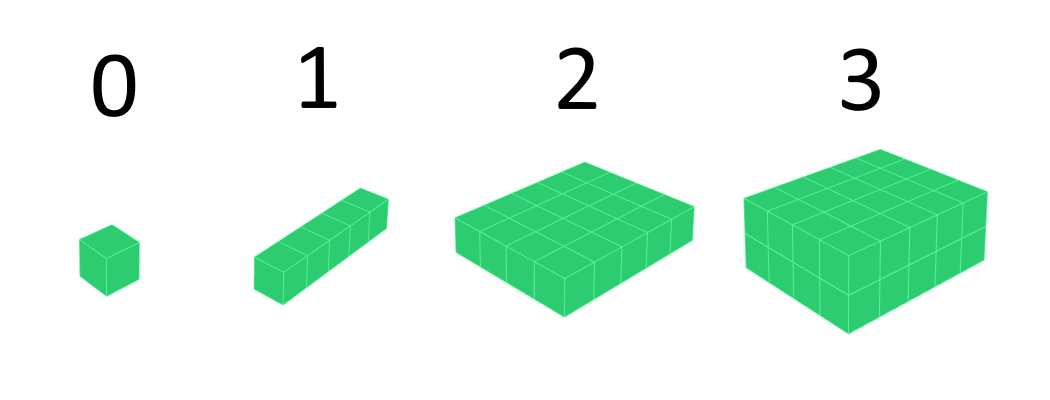

Let’s start slow. Imagine if you will, a box which “contains” a real-valued variable. We can say this represents a scalar \(A = \alpha \in \mathbb{R}\).

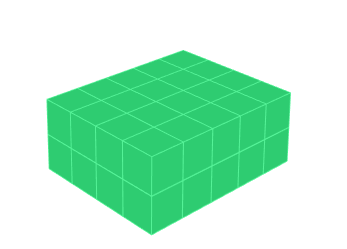

Tensor of order 0¶

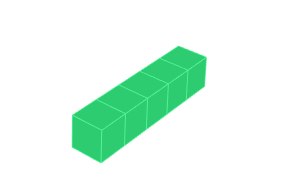

Now, let’s copy the box a certain number of times along a single dimension. Say, 5 times. This will represent a vector \(A = \bar{a} \in \mathbb{R}^{5}\). It has 5 variables, which we can index as \(A_0, A_1, \dots, A_4\).

Tensor of order 1¶

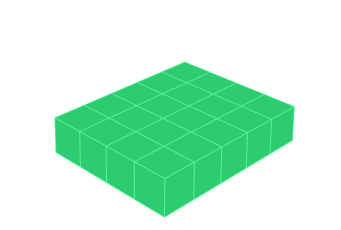

Let’s copy this vector 4 times along another dimension. This now becomes a 5 x 4 matrix \(A \in \mathbb{R}^{5 \times 4}\). We index each variable as \(A_{i, j}\) where \(i \in \{0, 1, \dots, 4\}\) and \(j \in \{0, 1, \dots, 3\}\).

Tensor of order 2¶

Let’s keep going, and copy this matrix 2 times along the z-axis, to get an order-3 tensor, i.e. a cuboid of variables \(\mathcal{A} \in \mathbb{R}^{5 \times 4 \times 2}\).

Tensor of order 3¶

Let’s just review our progression so far:

Tensors of order 0, 1, 2, 3¶

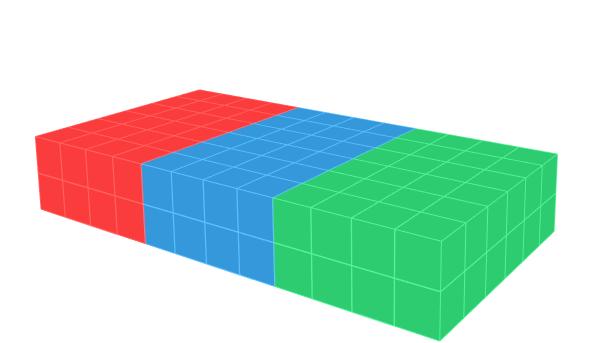

What’s our next step? We seem to have run out of dimensions! But this is only because 3D is the limit of human comprehension when it comes to axes of infinite length. It we want to visualize how the 5D world, we’re out of luck (at least I am).

However, in real-life problems, your data is finite! We can use this trick to visualize an order-4 tensor, by copying the (finite) cuboid a certain number of times along an existing axis. Let’s say we copy it 3 times and get a tensor \(\mathcal{A} \in \mathbb{R}^{5 \times 4 \times 2 \times 3}\). I have used different colors in the figure below to demark where the cuboid was copied.

Tensor of order 4¶

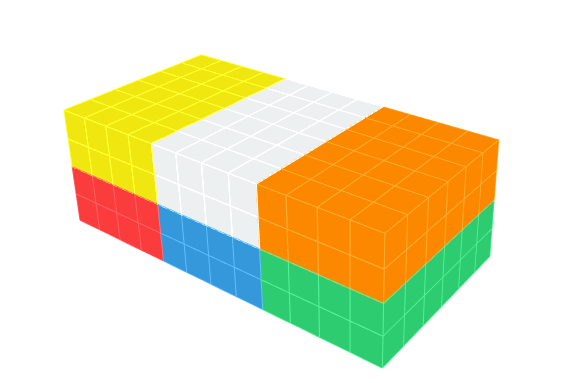

We can continue using this process, and create tensors of higher and higher order by copying the entire structure a \(N\) times. \(N\) now becomes the length of the newest dimension. E.g. we copy the 4D tensor above 2 times to get \(\mathcal{A} \in \mathbb{R}^{5 \times 4 \times 2 \times 3 \times 2}\).

Tensor of order 5¶

- We thus define a general tensor of order \(d\) using the notation \(\mathcal{A} \in \mathbb{R}^{N_1, N_2, \dots, N_d}\).

This notation should help clarify the confusion that occasionally occurs when we talk of “vectors with d dimensions” versus “tensors with d dimensions”. The former usually means \(\bar{a} \in \mathbb{R}^{d}\) whereas the latter means \(\mathcal{A} \in \mathbb{R}^{N_1, N_2, \dots, N_d}\).

Remember, each of these boxes in the figures above is a variable. It has a particular range of values it takes. For lower order tensors (vectors especially) it is possible that each variable has its own range, as we had in the previous example of housing data. However, for higher-order tensors, usually starting with matrices, each variable tends to have the same range, e.g. 0-255 for each pixel in our grayscale image of Abraham Lincoln.

Even for vectors, where the ranges can be different, we usually tend to normalize each variable to the same range as a pre-processing step. Usually the range \([0, 1]\) or \([-1, 1]\) is chosen. This is done to speed up certain optimization algorithms (e.g. gradient descent).

- We now revisit the definition we stated at the beginning: a tensor is a extension of a vector, which is itself an extension of a scalar. To speak in general terms:

A scalar is a single real-value in a particular range, i.e. it is a single variable.

A vector is an arrangement of a variable number of variables (scalars), along a single dimension.

A tensor is an arrangement of a variable number of variables (scalars), along a variable number of dimensions.

Side note: I drew all the above diagrams using VoxelBuilder. It’s pretty fun, you should try it out!

Rank isn’t order!¶

In much of the literature (and blogs), the word “rank” and “order” are used interchangeably when discussing the number of dimensions of a tensor. However, since rank has an alternate definition which is completely different from the order of a tensor, I will prefer to use “order” to describe the number of dimensions of a tensor (which I will denote as \(d\)).